The Two Skyscrapers Who Decided to Have a Child

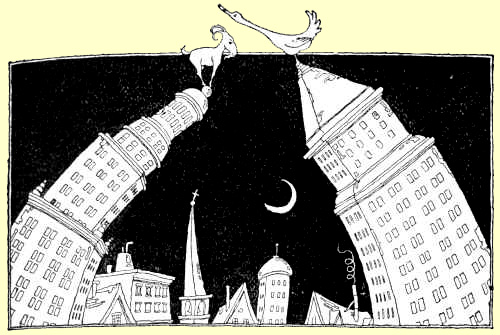

Two skyscrapers stood across the street from each other in the Village

of Liver-and-Onions. In the daylight when the streets poured full of people

buying and selling, these two skyscrapers talked with each other the same

as mountains talk.

In the night time when all the people buying and selling were gone home

and there were only policemen and taxicab drivers on the streets, in the night

when a mist crept up the streets and threw a purple and gray wrapper over

everything, in the night when the stars and the sky shook out sheets of

purple and gray mist down over the town, then the two skyscrapers leaned

toward each other and whispered.

Whether they whispered secrets to each other or whether they whispered

simple things that you and I know and everybody knows, that is their secret.

One thing is sure: they often were seen leaning toward each other and

whispering in the night the same as mountains lean and whisper in the night.

High on the roof of one of the skyscrapers was a tin brass goat looking out

across prairies, and silver blue lakes shining like blue porcelain breakfast plates,

and out across silver snakes of winding rivers in the morning sun. And high

on the roof of the other skyscraper was a tin brass goose looking out across

prairies, and silver blue lakes shining like blue porcelain breakfast plates, and

out across silver snakes of winding rivers in the morning sun.

Now the Northwest Wind was a friend of the two skyscrapers. Coming so far,

coming five hundred miles in a few hours, coming so fast always while the

skyscrapers were standing still, standing always on the same old street corners

always, the Northwest Wind was a bringer of news.

“Well, I see the city is here yet,” the Northwest Wind would whistle to the

skyscrapers.

And they would answer, “Yes, and are the mountains standing yet way out

yonder where you come from, Wind?”

“Yes, the mountains are there yonder, and farther yonder is the sea, and the

railroads are still going, still running across the prairie to the mountains, to the sea,

” the Northwest Wind would answer.

And now there was a pledge made by the Northwest Wind to the two skyscrapers.

Often the Northwest Wind shook the tin brass goat and shook the tin brass

goose on top of the skyscrapers.

“Are you going to blow loose the tin brass goat on my roof?” one asked.

“Are you going to blow loose the tin brass goose on my roof?” the other asked.

“Oh, no,” the Northwest Wind laughed, first to one and then to the other, “if I ever

blow loose your tin brass goat and if I ever blow loose your tin brass goose, it will

be when I am sorry for you because you are up against hard luck and there is

somebody’s funeral.”

So time passed on and the two skyscrapers stood with their feet among the

policemen and the taxicabs, the people buying and selling,—the customers with

parcels, packages and bundles—while away high on their roofs stood the goat and

the goose looking out on silver blue lakes like blue porcelain breakfast plates and

silver snakes of rivers winding in the morning sun.

So time passed on and the Northwest Wind kept coming, telling the news and

making promises.

So time passed on. And the two skyscrapers decided to have a child.

And they decided when their child came it should be a free child.

“It must be a free child,” they said to each other. “It must not be a child standing

still all its life on a street corner. Yes, if we have a child she must be free to run

across the prairie, to the mountains, to the sea. Yes, it must be a free child.”

So time passed on. Their child came. It was a railroad train, the Golden Spike

Limited, the fastest long distance train in the Rootabaga Country. It ran across

the prairie, to the mountains, to the sea.

They were glad, the two skyscrapers were, glad to have a free child running away

from the big city, far away to the mountains, far away to the sea, running as far as

the farthest mountains and sea coasts touched by the Northwest Wind.

They were glad their child was useful, the two skyscrapers were, glad their child

was carrying a thousand people a thousand miles a day, so when people spoke

of the Golden Spike Limited, they spoke of it as a strong, lovely child.

Then time passed on. There came a day when the newsies yelled as though

they were crazy. “Yah yah, blah blah, yoh yoh,” was what it sounded like to the

two skyscrapers who never bothered much about what the newsies were yelling.

“Yah yah, blah blah, yoh yoh,” was the cry of the newsies that came up again

to the tops of the skyscrapers.

At last the yelling of the newsies came so strong the skyscrapers listened and

heard the newsies yammering, “All about the great train wreck! All about the Golden

Spike disaster! Many lives lost! Many lives lost!”

And the Northwest Wind came howling a slow sad song. And late that afternoon

a crowd of policemen, taxicab drivers, newsies and customers with bundles, all

stood around talking and wondering about two things next to each other on the

street car track in the middle of the street. One was a tin brass goat. The other was

a tin brass goose. And they lay next to each other.

Two skyscrapers stood across the street from each other in the Village

of Liver-and-Onions. In the daylight when the streets poured full of people

buying and selling, these two skyscrapers talked with each other the same

as mountains talk.

In the night time when all the people buying and selling were gone home

and there were only policemen and taxicab drivers on the streets, in the night

when a mist crept up the streets and threw a purple and gray wrapper over

everything, in the night when the stars and the sky shook out sheets of

purple and gray mist down over the town, then the two skyscrapers leaned

toward each other and whispered.

Whether they whispered secrets to each other or whether they whispered

simple things that you and I know and everybody knows, that is their secret.

One thing is sure: they often were seen leaning toward each other and

whispering in the night the same as mountains lean and whisper in the night.

High on the roof of one of the skyscrapers was a tin brass goat looking out

across prairies, and silver blue lakes shining like blue porcelain breakfast plates,

and out across silver snakes of winding rivers in the morning sun. And high

on the roof of the other skyscraper was a tin brass goose looking out across

prairies, and silver blue lakes shining like blue porcelain breakfast plates, and

out across silver snakes of winding rivers in the morning sun.

Now the Northwest Wind was a friend of the two skyscrapers. Coming so far,

coming five hundred miles in a few hours, coming so fast always while the

skyscrapers were standing still, standing always on the same old street corners

always, the Northwest Wind was a bringer of news.

“Well, I see the city is here yet,” the Northwest Wind would whistle to the

skyscrapers.

And they would answer, “Yes, and are the mountains standing yet way out

yonder where you come from, Wind?”

“Yes, the mountains are there yonder, and farther yonder is the sea, and the

railroads are still going, still running across the prairie to the mountains, to the sea,

” the Northwest Wind would answer.

And now there was a pledge made by the Northwest Wind to the two skyscrapers.

Often the Northwest Wind shook the tin brass goat and shook the tin brass

goose on top of the skyscrapers.

“Are you going to blow loose the tin brass goat on my roof?” one asked.

“Are you going to blow loose the tin brass goose on my roof?” the other asked.

“Oh, no,” the Northwest Wind laughed, first to one and then to the other, “if I ever

blow loose your tin brass goat and if I ever blow loose your tin brass goose, it will

be when I am sorry for you because you are up against hard luck and there is

somebody’s funeral.”

So time passed on and the two skyscrapers stood with their feet among the

policemen and the taxicabs, the people buying and selling,—the customers with

parcels, packages and bundles—while away high on their roofs stood the goat and

the goose looking out on silver blue lakes like blue porcelain breakfast plates and

silver snakes of rivers winding in the morning sun.

So time passed on and the Northwest Wind kept coming, telling the news and

making promises.

So time passed on. And the two skyscrapers decided to have a child.

And they decided when their child came it should be a free child.

“It must be a free child,” they said to each other. “It must not be a child standing

still all its life on a street corner. Yes, if we have a child she must be free to run

across the prairie, to the mountains, to the sea. Yes, it must be a free child.”

So time passed on. Their child came. It was a railroad train, the Golden Spike

Limited, the fastest long distance train in the Rootabaga Country. It ran across

the prairie, to the mountains, to the sea.

They were glad, the two skyscrapers were, glad to have a free child running away

from the big city, far away to the mountains, far away to the sea, running as far as

the farthest mountains and sea coasts touched by the Northwest Wind.

They were glad their child was useful, the two skyscrapers were, glad their child

was carrying a thousand people a thousand miles a day, so when people spoke

of the Golden Spike Limited, they spoke of it as a strong, lovely child.

Then time passed on. There came a day when the newsies yelled as though

they were crazy. “Yah yah, blah blah, yoh yoh,” was what it sounded like to the

two skyscrapers who never bothered much about what the newsies were yelling.

“Yah yah, blah blah, yoh yoh,” was the cry of the newsies that came up again

to the tops of the skyscrapers.

At last the yelling of the newsies came so strong the skyscrapers listened and

heard the newsies yammering, “All about the great train wreck! All about the Golden

Spike disaster! Many lives lost! Many lives lost!”

And the Northwest Wind came howling a slow sad song. And late that afternoon

a crowd of policemen, taxicab drivers, newsies and customers with bundles, all

stood around talking and wondering about two things next to each other on the

street car track in the middle of the street. One was a tin brass goat. The other was

a tin brass goose. And they lay next to each other.